A bullet from a drug cartel, the best goalkeeper in World Cup history, and Higuaín's cradle: Shakhtar's opponent has a more storied past than it appears.

Conte-Verde

In Brittany, particularly in Brest, it's quite simple – there's a large port and ships.

Father took Alex Teppo to sea from the age of 15 – Toulon, Tunisia, Rochefort; he saw the entire Mediterranean before finishing school.

In 1930, Teppo even calmed the coaches aboard the Conte-Verde – the ship on which France and Jules Rimet set off to Uruguay for the first-ever World Cup. Although Jules came up with the idea, he himself hesitated – would everything fall apart at the last moment?

Teppo started playing in Brest but quickly gained fame and moved to Red Star in Paris.

When there were no matches, he helped a customs inspector who took a two-month unpaid leave for Uruguay.

Perhaps he sensed something.

Although Alex played without gloves, barehanded, he saved his team countless times, diving into the fiercest tackles. Once against Mexico, a striker hit him so hard on the head that Teppo lost consciousness for an hour – and it was all good, no complaints.

Uruguay loved him for that bravery and he was the only European included in the symbolic World Cup team.

Meanwhile, France respected him so much that after the war, they entrusted him with training the generation of Fontaine, Kopa, and Piantoni, which shone at the 1958 World Cup even though he continued to work in customs. Seriously – in the 60s, he rose to chief inspector, uncovering a couple of fraudulent schemes.

This was the first legend of Brest – remarkable in every aspect.

Not the ugliest city

During Teppo's time, there was no professional club in Brest – it appeared in 1958.

The first serious considerations for something big in Brittany came in the 80s – President François Ivinek secured funding from the Leclerc supermarket chain and decided he would become Brittany's Tapie.

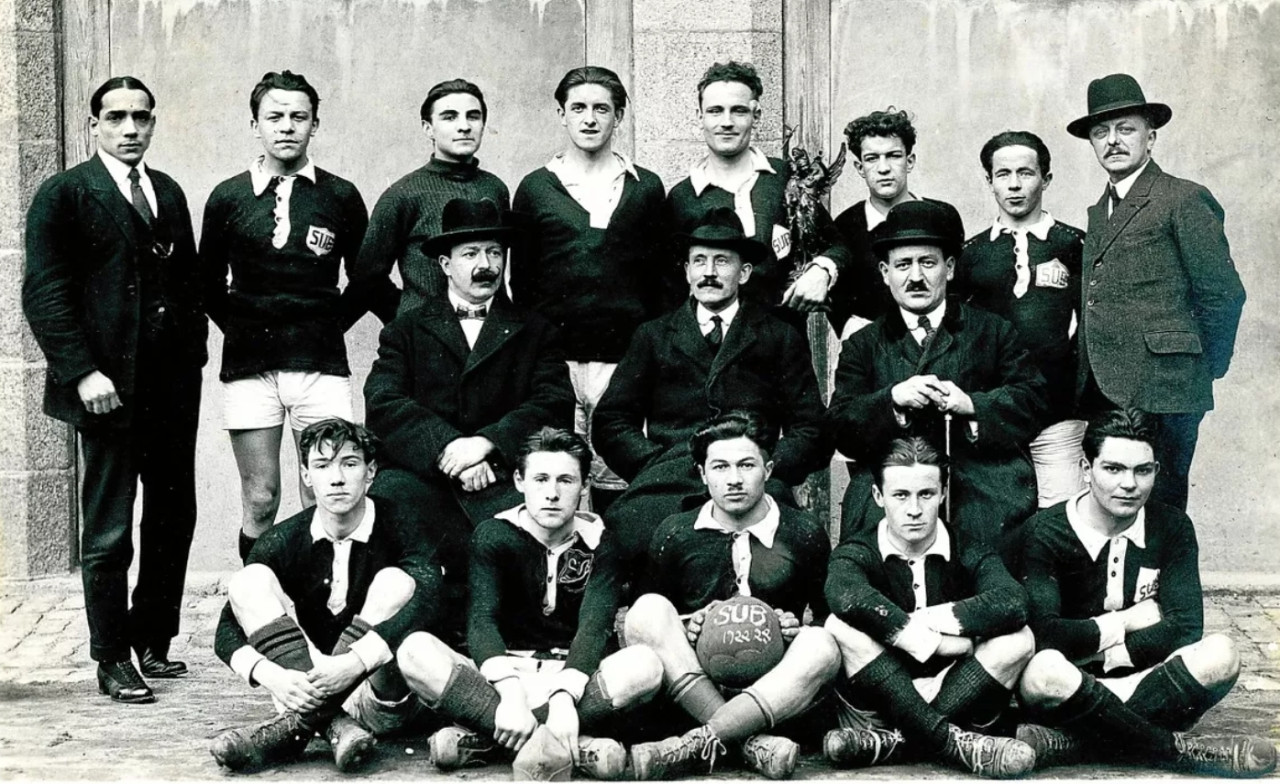

Immediately after the 1986 World Cup, Ivinek brought to François Le Blé the author of the final goal, José Luis Brown, as well as the megatalented Júlio César, who later made a name for himself at Juventus and Borussia.

At the very first training, Higuaín showed what he could do – several players ended up with bruises, and one limped off to the doctors.

He also recalls that Jorge adapted perfectly in Brittany – quickly learned the language, played pétanque, and spent weekends with the team on the coast at the homes of familiar fishermen, where they washed down fresh oysters with wine.

The whole team welcomed Higuaín when his wife gave birth to their son – Gonzalo – in Brest.

Raymond Domenech called Gonzalo twice – in 2006 for the French national team and in 2016 for the unofficial Brittany team. Both times, there was no response.

A bullet in an envelope

Ivinek tried hard, but the club was in turmoil. In 1987, they were 8th in Ligue 1, but by 1988, they had dropped to Ligue 2.

Partially to blame was the transfer of Roberto Cabanas – for a hefty $350,000, but the player was nowhere to be found.

August – none. September – none. October – still none.

On November 3, 1987, Ivinek went after Cabanas himself, as he was too unaware of the situation. América Cali was not just a club – it was managed by the largest drug cartel across the ocean, which had deep roots in power, and by December 4, the Frenchman was accused of fraud and thrown into jail.

Thankfully, it ended without casualties.

François was brought to a house that resembled a fortress – surrounded by gunmen, machine guns, and grenade launchers. Inside awaited brothers Miguel and Gilberto Rodriguez – leaders of the Cali cartel. Despite the Frenchman's assurances that the deal was done, they claimed they had signed nothing.

Ivinek was saved from the consequences by Jacques Chirac, who was then the Prime Minister. When he was informed about the situation, he told the Colombians that if François did not leave, none of their riders would compete in the Tour de France. For the cartel, that was a blow – they had high hopes for their cycling team.

So, Ivinek was returned – without documents, under a false name, and even transiting through Venezuela.

Cabanas was also released, but a bit later – and he scored over 40 goals for Brest, bringing them back to the elite in 1989.

Additionally, a strange letter arrived at the Open office around that time – it contained a 9 mm bullet and a note: "We are always waiting for you again."

Liquidation

Whether it was that bullet or the breakup with Leclerc that affected Ivinek, but by the early 90s, the Latin Americans in Brest became history. Now the club relied on its own.

And they had talent, it must be said.

Vincent Guérin, Patrick Colleter, and Paul Le Guen later brought trophies to PSG. Promising Bernard Lama moved from Metz to François Le Blé. In the youth team, Stéphane Guivarc'h and Claude Makélélé were maturing.

Later, Ivinek said that this team lacked 2-3 years to dominate Ligue 1.

David Ginola, who was also there, agrees with that statement:

Ultimately, Ginola revitalized in Brittany, played for the French national team; he indulged in, as he says, the most delicious lobsters in the world.

He also emerged as a leader during the club's liquidation in 1991.

The essence is that Ivinek finally went bankrupt and handed Brest over to a little-known investor, who did not pay players' salaries but wanted to profit from their sale. The league was not opposed, but Ginola led the players who said "no."

Consequently, on December 6, 1991, the court liquidated the club, and the players were released for free, while the unscrupulous owners received nothing. The new Brest became a youth team that played in amateur leagues – they were freed from old debts. Ginola soon moved to PSG, and Ivinek fled to Spain, where he lamented for a long time:

Hooligan

Thus, Brest returned to the mire, where it existed until the 80s. The club was forgotten.

You might ask – hey, how did Franck Ribéry end up here at the age of 21?

Well, it was because he was a wild one.

He sent coaches left and right packing – that's how he got expelled from Lille's academy. Simultaneously, Franck married young, converted to Islam, worked in construction, and spoke incomprehensibly – in the criminal dialect "shty," like all the workers in Boulogne-sur-Mer.

In Brest, coaches immediately "met" Ribéry when he locked them in the changing room and wouldn’t let them out, laughing behind the door.

But alongside that, how he played!

The decisive moment for Ribéry was the match in the 1/8 final of the cup against Nantes – no chances for the Pirates, who logically lost 0:4, but after the game, everyone spoke only about Franck:

At that time, he chose Metz – closer to his homeland.

However, before the transfer, Franck led Brest to Ligue 2, finishing the season with 23 assists in National. This record of his remains unbroken.

Oriac, who later led the Pirates' U17 team, assures that in Brest they cheered for Ribéry at Marseille, Bayern, and Fiorentina. His appearance inspired them; it reminded the city how to play football and where Brest had played before.

After Ribéry in National, they never fell again.

By 2010, the Pirates returned to the elite – for the first time in 19 years. In 2024, Brest played in the Champions League – for the first time in history.

The current squad may not have talents worthy of